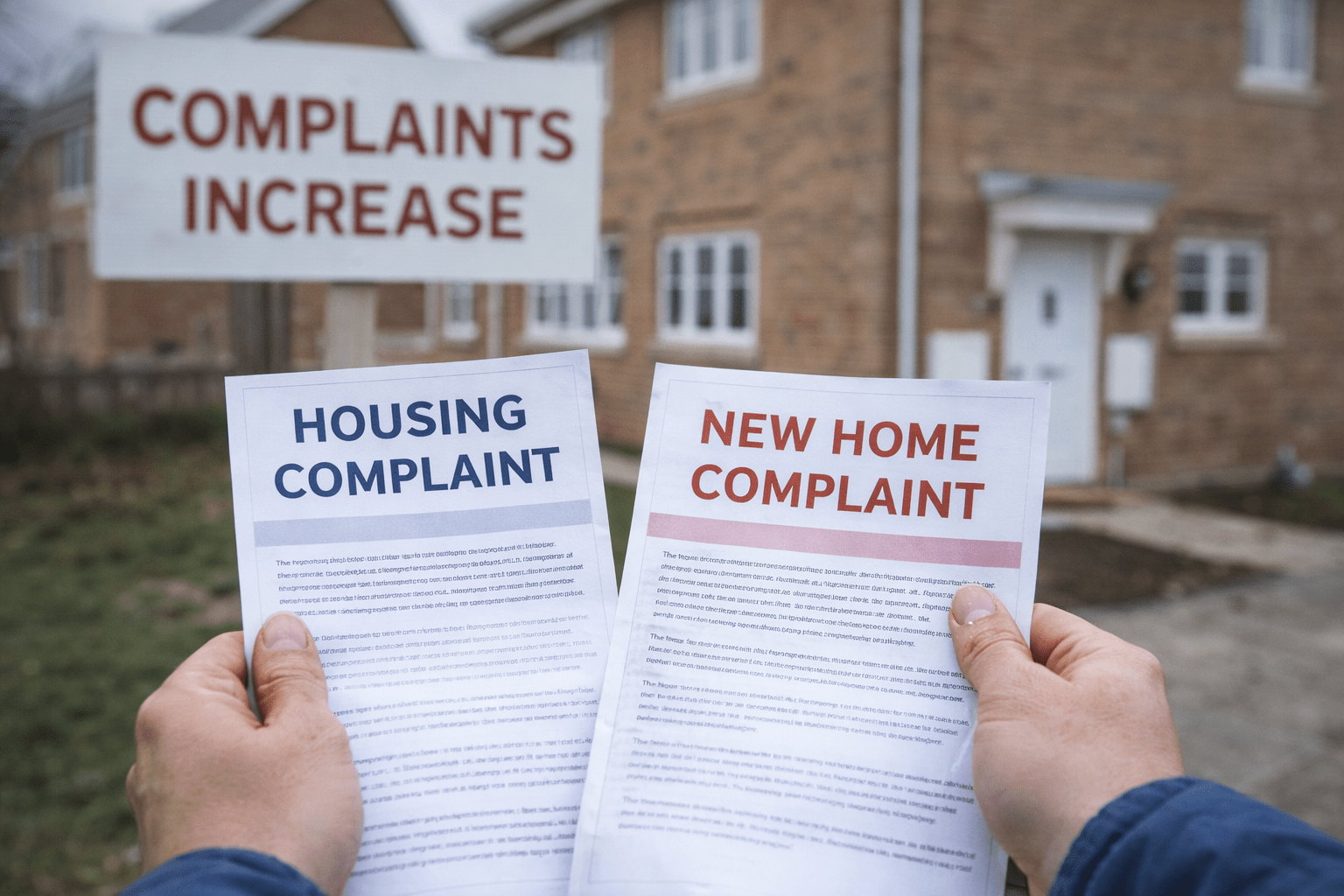

In UK housing, complaints were once treated mainly as a necessary back-end process. Something went wrong, a resident escalated it, the organisation worked through its stages, the Ombudsman might become involved, and eventually the case was closed. Today that picture looks very different.

Complaint volumes have continued to rise across both social housing and new build. Some of that increase reflects positive developments, such as clearer routes for residents to raise concerns and stronger expectations around complaint handling. The more important shift is how this information is now interpreted. Complaint data is no longer viewed purely as a regulatory outcome. It is increasingly seen as a visible indicator of communication quality, coordination across teams, and how residents experience life after they move into their homes. Boards, regulators, journalists and residents are reading complaint trends as evidence of how organisations behave when things go wrong, not just how often issues occur.

Complaints as early warning signals rather than isolated cases

When similar issues appear repeatedly in complaints, they rarely point to one-off mistakes. Instead, they reveal underlying weaknesses. Clusters of cases about property condition, missed appointments, unclear communication or delays in repairs usually indicate gaps in coordination and ownership. These patterns often affect whole developments or portfolios rather than individual homes.

In new build delivery, the expansion of formal redress and quality frameworks has reinforced this direction. The question is moving away from whether a complaint can eventually be closed, and towards what recurring themes in the data say about aftercare maturity, resident experience and operational resilience. In many situations, the technical issue is not the main driver of dissatisfaction. The frustration comes from slow responses, unclear responsibility or the sense that a problem is being passed between teams rather than resolved.

The gap between closure on paper and confidence in reality

A case can be categorised as resolved in procedural terms while still damaging trust. Residents place as much weight on how an issue is handled as they do on the final outcome. Confidence grows when ownership is visible, explanations are clear and communication is timely. It declines when residents feel they are chasing updates, repeating information or trying to understand who is responsible for progress.

Greater transparency has made this gap more visible. Ombudsman findings, complaint handling performance reports and public case summaries are now widely read and frequently discussed. At the same time, residents share their experiences in online groups, forums and local communities. As a result, the journey through the complaints process often has a longer influence on perception than the original defect or service failure that triggered it.

Complaints as part of organisational reputation

Taken together, these trends mean that complaints now act as a benchmark for trust as much as a compliance mechanism. High volumes in particular categories, or a significant proportion of upheld cases, quickly become part of how an organisation is viewed. Equally, visible improvement in complaint handling, a reduction in repeat themes and clear evidence of learning from failures can strengthen credibility.

In this context, complaints are not only about resolving disputes. They are signals about whether responsibilities are joined up, whether residents feel heard and whether aftercare is being treated as part of the delivery journey rather than something separate from it. The organisations responding well are those who use complaint data to highlight weak points in communication, workflow and ownership, and then address the causes rather than just the symptoms.

What this means for 2026

The implication is not that every complaint represents failure, or that rising volumes always indicate declining standards. It is that complaints have shifted from a private, back-office process to a visible part of how performance, culture and accountability are judged.

For housing providers, developers and principal contractors, this means recognising that the complaints system now plays a role in shaping reputation as well as regulation. Treating complaint trends as operational insight, strengthening clarity around responsibility and improving how residents experience the process are becoming central to maintaining trust.

If residents now shape perception through their lived experience of new homes, complaint systems are increasingly where that experience is recorded, examined and remembered. How organisations respond to that reality will define how they are judged in the years ahead.