A recent article highlighted how unprepared the UK’s housing stock is for hotter summers and more frequent heatwaves. Overheating is now being treated as a direct health risk, not just an inconvenience. That shift matters because it moves housing performance out of the “comfort” category and firmly into the “safety” one.

For years, the conversation around housing quality has focused almost entirely on winter conditions. Cold, damp, mould and insulation standards have dominated policy and funding. But climate change does not just bring harsher winters. It also brings prolonged heat, sudden humidity swings and weather patterns that place very different stresses on buildings.

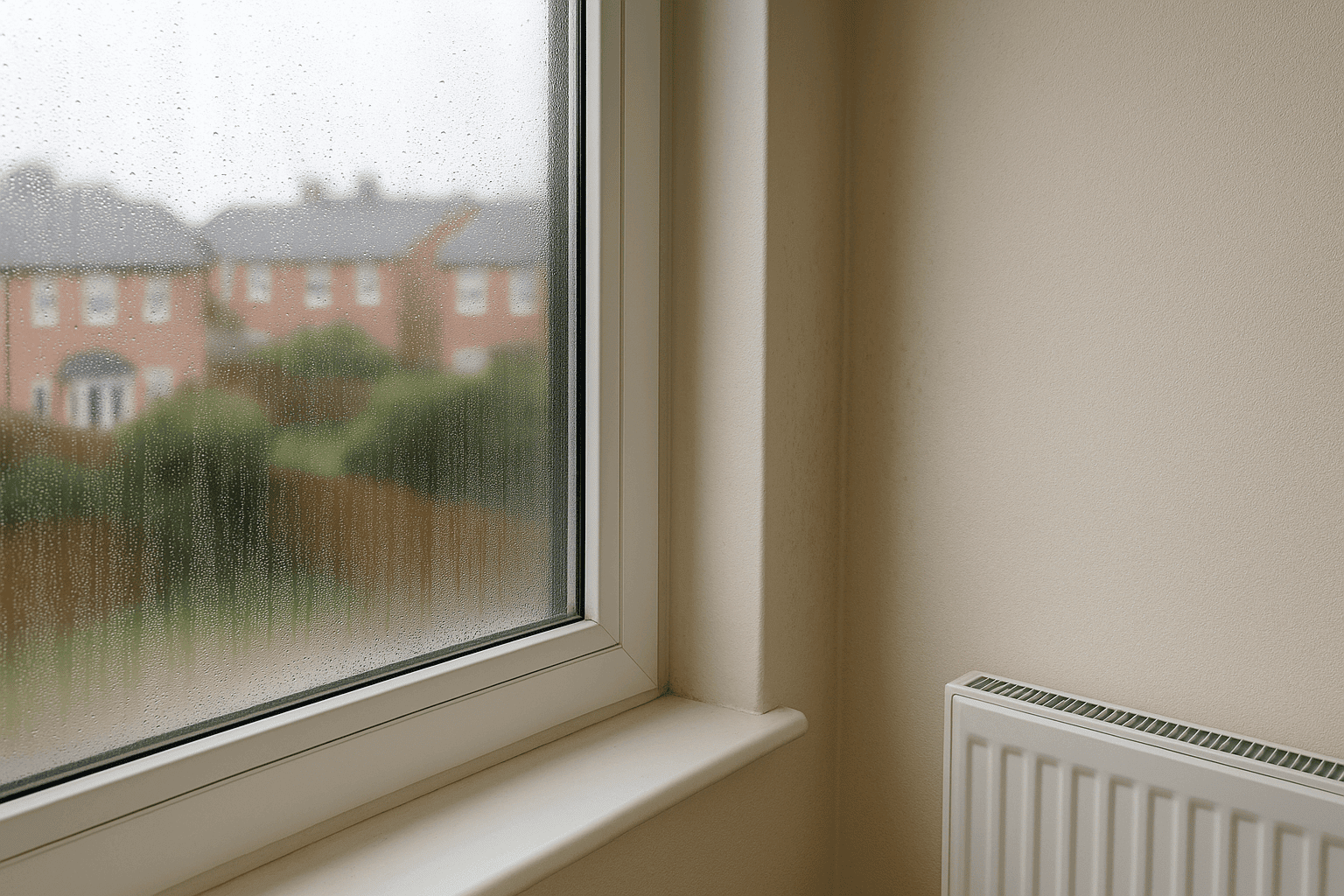

Many homes were never designed with summer heat in mind. Smaller windows, high insulation levels and limited airflow might help retain warmth in winter, but they become liabilities when temperatures rise. The same construction decisions can also worsen condensation and moisture issues when airflow is poor. A home can end up cold and damp in winter and dangerously hot in summer. Both conditions come from the same problem: buildings that are no longer suited to the environment they sit in.

Overheating and damp are often treated as separate issues. In reality, they are linked. Heat builds up in tightly sealed homes. Moisture has nowhere to escape. Ventilation systems struggle to cope with occupancy and changing weather. Insulation traps warmth where it once made sense to do so. The result is that homes start reacting badly to the very interventions meant to improve them.

That matters because housing is not static. It is one of the longest-lived assets in the country. Poor decisions made during design, construction or retrofit do not disappear after a few seasons. They affect health, energy costs and comfort for years.

It also matters because housing policy still tends to treat performance in silos. Energy efficiency is often divorced from ventilation. Moisture control is rarely considered alongside cooling. Climate adaptation gets talked about as a future issue, even though its effects are already visible in homes that overheat, trap humidity or fail to regulate temperature properly.

The answer is not more isolated improvements. It is joined-up thinking.

Homes need to be treated as systems, not as collections of parts. Insulation, ventilation, moisture control, shading, airflow and materials all interact. Improving one area without understanding the impact on another is how well-intended work creates new problems.

As legal and regulatory standards increase elsewhere in the sector, housing quality will increasingly be judged by outcomes rather than promises. Safe temperatures. Healthy air. Manageable moisture. Liveable spaces throughout the year. These are not preferences. They are becoming expectations.

This is especially relevant for landlords, developers and managers who may assume that changing standards only apply to certain tenures or funding streams. Experience suggests otherwise. Expectations always reach further than regulation. What becomes unacceptable in one part of housing rarely stays there for long.

That is why building performance can no longer be thought of as optional or seasonal. A home that performs well in January but fails in July is not truly high quality. A retrofit that cuts energy bills but increases overheating is not a success. A design that meets a short-term target but introduces long-term health risk is not fit for a changing climate.

The practical question now is how the sector manages this shift.

Better housing will not come from better slogans or one-off upgrades. It will come from understanding real world performance, tracking outcomes over time and making decisions based on how homes actually behave once people live in them.

This is where platforms like Ubrix increasingly matter. Not as part of the marketing conversation, but as part of the operational one. When teams can see patterns across buildings, monitor performance, track issues and learn from what happens after handover, housing quality stops being theoretical and starts becoming measurable.

That is what climate resilience looks like in practice. Not a policy document. A system that helps homes improve over time.

If housing is to remain safe in a changing climate, performance has to matter just as much as specification. What homes do in real weather counts more than what they promise on paper.